Behind the Scenes of Paris by the Book

In 2012, on the last day of my daughters' first trip to Paris, we wandered into a bookstore in the Marais that was about to close...

No. Start here: on the first day of that trip, my then almost-six-year old stood on the rue de Turenne, arms akimbo, face set, and declared: I've been here before...

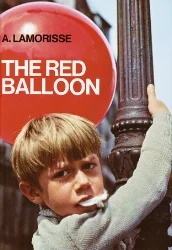

Or no, wait, start here: I'm six years old and my godmother has just given me an fascinating book about a boy in Paris, illustrated with photographs: The Red Balloon.

The truth is, wherever I start, I end up in the same place: Paris.

*

Confessions: though I've visited often, I've never lived in Paris. And neither has my youngest child. But we—and millions upon millions of other readers, particularly in America—feel as though we know the city well because we do know the city well, in our imaginations, and in the imaginations of authors we read, over and over again.

In 2012, my family and I went to Paris to test a hypothesis: that, thanks to all their reading, my young daughters knew Paris well enough that they could lead us around Paris. And for approximately two weeks, that's what the girls did. Instead of the usual guidebooks, we toted along a travel-ready set of Madeline books and a copy of The Red Balloon. (Or rather, the copy of The Red Balloon, that fraying childhood copy my godmother had given me.)

And off we went. Ludwig Bemelmans, the author and artist behind the Madeline series, led us through most of Paris' most familiar sites, everything from Sacre Coeur to the Luxembourg Gardens to, of course, the Eiffel Tower. Albert Lamorisse, the author and filmmaker behind The Red Balloon—which began life as a film, and won an Oscar in 1956—led us through less familiar parts of Paris, in particular, the labyrinthine heights of Ménilmontant, a hilly neighborhood northeast of Paris' monumental core.

The result? Magic. (And tired feet, and racing to find bathrooms, and too many Nutella crepes—but I’ve a whole page on this site devoted to the practicalities of touring Paris with kids.)

Truly, though, magic. Seeing Paris through their eyes—seeing Bemelmans’s and Lamorisse’s Paris come alive in their eyes—was an extraordinary experience. To draw on another children’s classic, Frank Baum’s Wizard of Oz, finding the real Paris behind the books we loved was a bit like pulling the curtain back and finding notthe wizard, but another Oz.

We took some wrong turns. We got lost. The girls always needed bathrooms when none were near and rain often rushed in when we’d counted on sun. We ate a few too many Nutella crepes and my wife and I drank not nearly enough wine. We went inside too few museums and encountered too many other tourists like us, moving about the city in packs.

But tourists as much as Parisians make Paris Paris. Adam Gopnik writes that Ludwig Bemelmans got more Americans to Paris than anyone in France realizes, and I think that’s right. But I also think that he got more people to Paris who never left the United States. Paris, for millions of readers, will only ever be a place they visit in imagination.

Gopnik also notes that Parisians are largely unfamiliar with Bemelmans, and I found that to be true. I asked the current proprietor of a bar Bemelmans once owned—whose walls the artist had covered in riotous murals, not unlike the famed Bemelmans Bar in New York—what it was like to own such a historic spot. He shrugged. The murals were long gone. I asked about Bemelmans. He shrugged. I went outside and took a picture of the historical plaque on the side of his building, which mentions Bemelmans’s brief ownership. I showed him. He shrugged.

Lamorisse, too, is arguably better known to Americans. Researchers who visit the Cinematheque française, the French national film center, leave their belongings in lockers that bear, instead of numbers, the names of famous directors. Francois Truffaut’s name appears there. So does Spike Lee’s. Lamorisse's does not. When I asked two policewomen in Ménilmontant about The Red Balloon—with book of photographs in hand—they had no idea what I was talking about. (That said, someone knows, because around the corner, on the side of a building at 36 rue Henri Chevreau, someone has painted a red balloon flying up, up into the sky.)

All this led me to think: what would it be like to live in a place that you’ve only lived in your mind? What would it be like to move into your mind? To move into your mind’s Paris?

In 2012, on the last day of my daughters' first trip to Paris, we wandered into a bookstore in the Marais. The owner half-jokingly offered to sell it to us. The girls looked around. My wife looked at me.

I looked at all those books, all these Parises, and thought, this is where we start.

Additional resources

Do I have thoughts about how to tour Paris with kids? Yes, I do. And so do my kids. If you'd like to read the article I originally wrote for the Wall Street Journal about our Paris book adventure, visit their archives (paywall).

If you'd like to tour--virtually or in person--the Paris of Madeline or The Red Balloon, I've customized some Google maps for just this purpose.

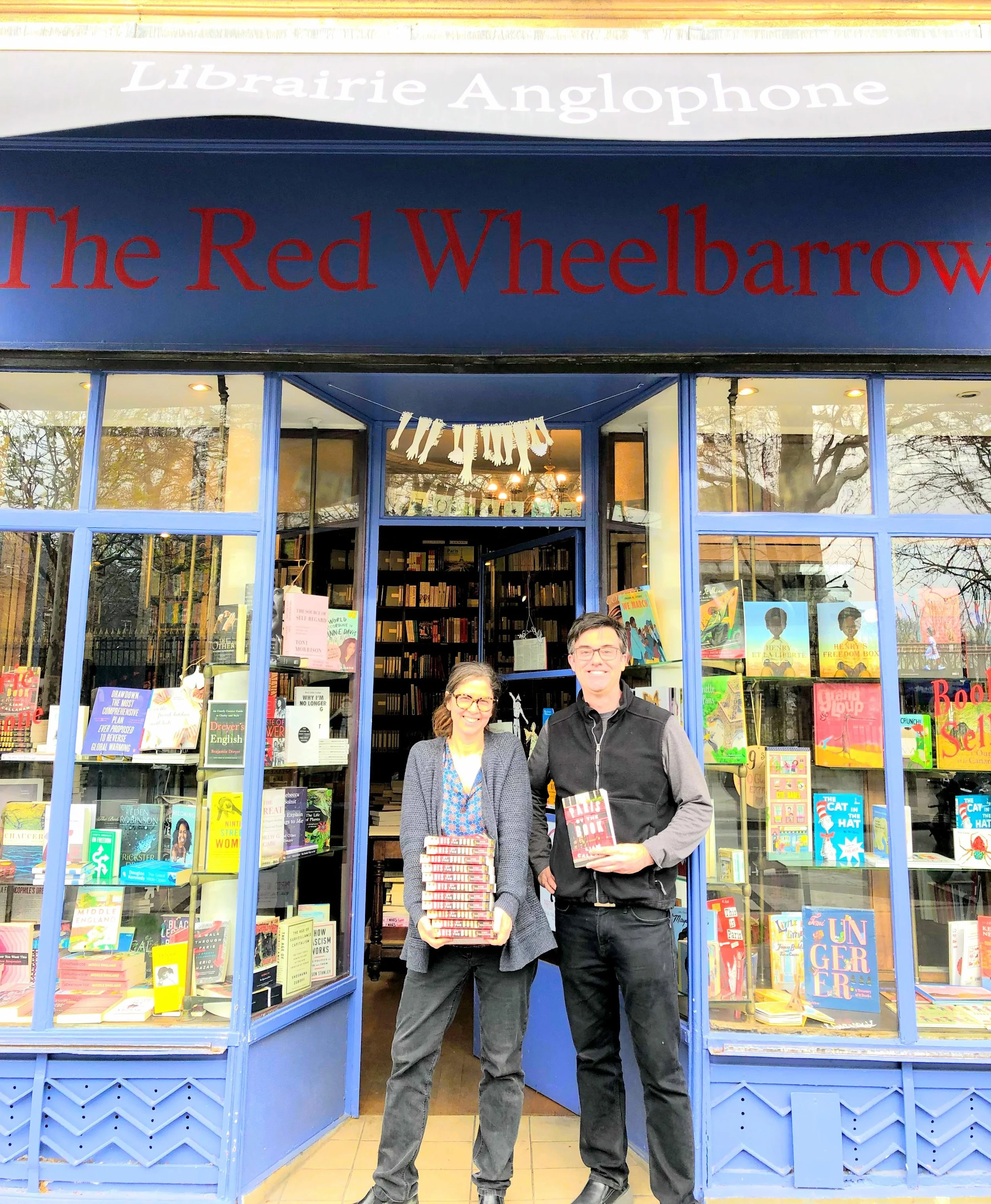

We didn’t buy the store, but it has happily reopened on the Left Bank. It’s called The Red Wheelbarrow and it’s at no. 9, rue des Medicis.

If you’d like to visit Bemelmans’s old restaurant in Paris, it does indeed still exist, though in a completely different form, sans Bemelmans’s murals. It’s currently called Les Deux Colombes and is located at no. 4, rue de la Colombe, not far from Notre Dame. (If you’d like to learn more about the history of the building—and why the street is named for doves—see here.)