My 14 year old daughter had a problem to solve in French class (of course they take French!) the other week: she was to pair up with a classmate and craft a short back-and-forth dialogue for the class. That wasn't the problem, rather, after everyone chose partners, she found she was in a group of three. What to do? My daughter thought the answer obvious: they'd write up a dialogue where two girls were interested in the same guy. And he's interested in...

I'll leave things there, but Edith Wharton (1862-1937 )wouldn't have, and across dozens of novels, stories and novellas, never did. Though known most now for her New York Gilded Age Novels, she's always interested me for her writings on, in, and around Paris. If the Age of Innocence or The House of Mirth ever intimidated you, first, get over that, and second, start with one of her novellas, like today's recommendation, Madame de Treymes. It distills all of Wharton's most famous elements--class, money, religion, straitlaced society--into a 90 pp. novella set in Paris. Meet handsome, wealthy American bachelor John Durham, whose "European visits were infrequent enough to have kept unimpaired the freshness of his eye" and so he was

always struck anew by the vast and consummately ordered spectacle of Paris: by its look of having

been boldly and deliberately planned as a background for the enjoyment of life, instead of being forced into grudging concessions to the festive instincts, or barricading itself against them in unenlightened ugliness, like his own lamentable New York.

But to-day, if the scene had never presented itself more alluringly, in that moist spring bloom between showers, when the horse-chestnuts dome themselves in unreal green against a gauzy sky, and the very dust of the pavement seems the fragrance of lilac made visible--to-day for the first time the sense of a personal stake in it all, of having to reckon individually with its effects and influences, kept Durham from an unrestrained yielding to the spell. Paris might still be--to the unimplicated it doubtless still was--the most beautiful city in the world; but whether it were the most lovable or the most detestable depended for him, in the last analysis, on the buttoning of the white glove over which Fanny de Malrive still lingered.

The unimplicated! Unexpected, and unexpectedly perfect, word choices like that abound through the headlong rush of the next 90 pp., where Durham pursues Fanny, whom he could happily be with--and she with him--if only it weren't for the fact that she is already married. So, then, a divorce? Bien-sûr, except there's one small obstacle; perhaps Fanny's sister-in-law the eponymous Madame de Treymes, might be able to help?

I won't tell you how it ends--if you know Wharton, you know how it ends--although I do differ from many readers and critics when I say that I find a strange sense of possibility lurking in the blank part of the page beneath the final paragraph. Maybe all is not lost, maybe the sunny Paris of the first page is still sunny if--oh, but now I've implicated myself. No matter.

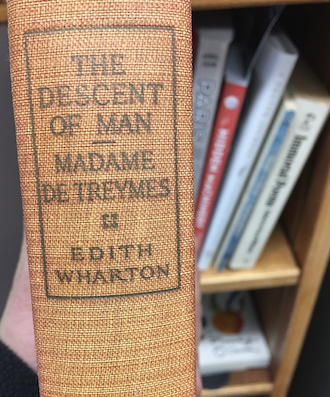

(Enjoy here if you want the raw text of the book (h/t to the Edith Wharton Society), or find yourself a pleasingly (if unfairly) dusty volume at your local library like the 1907 Scribner's edition pictured here.)